Explore “The Giants Among Us”: massive large crystals. Find out how they form and where to visit museums showcasing their captivating display exhibits.

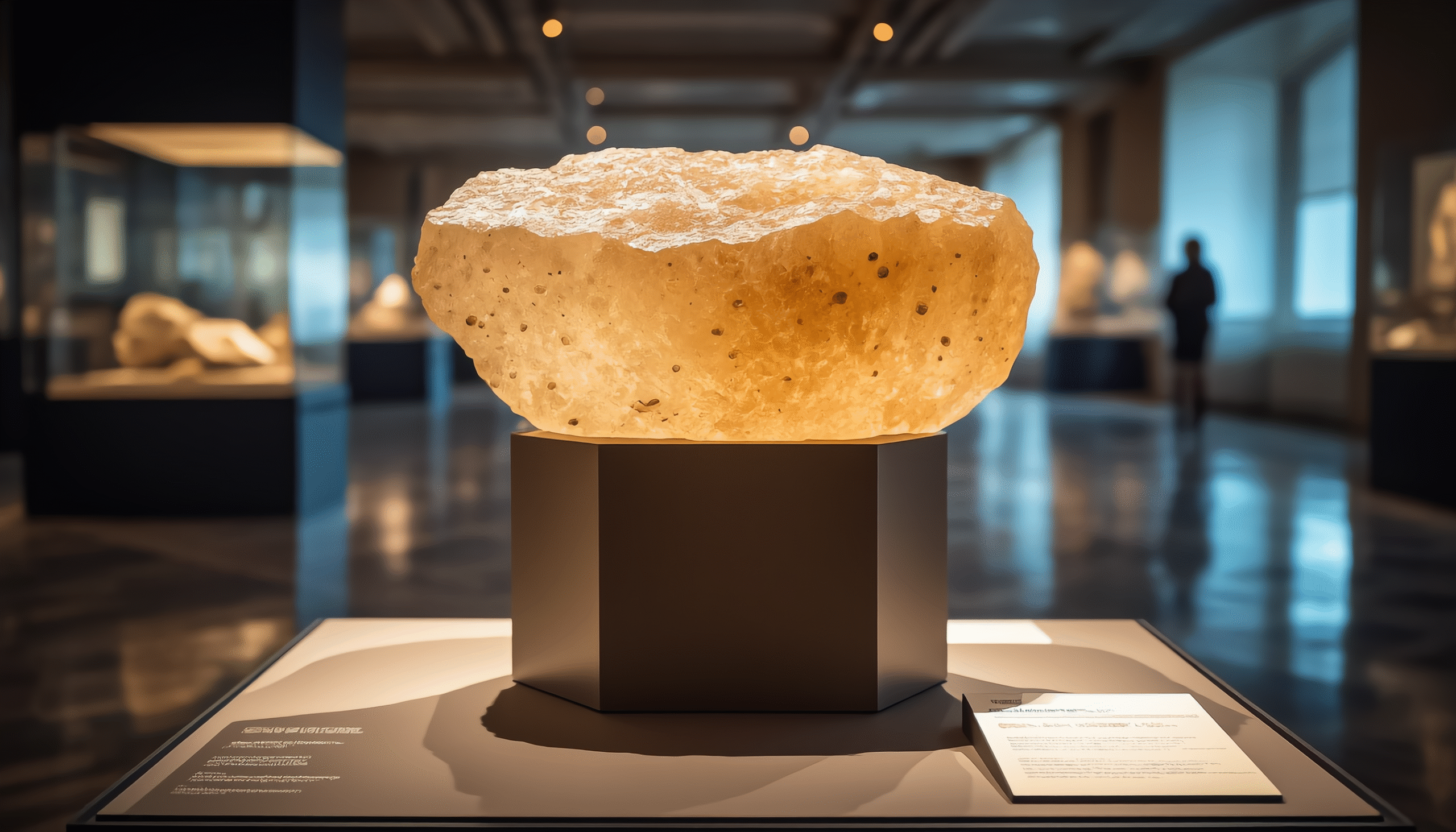

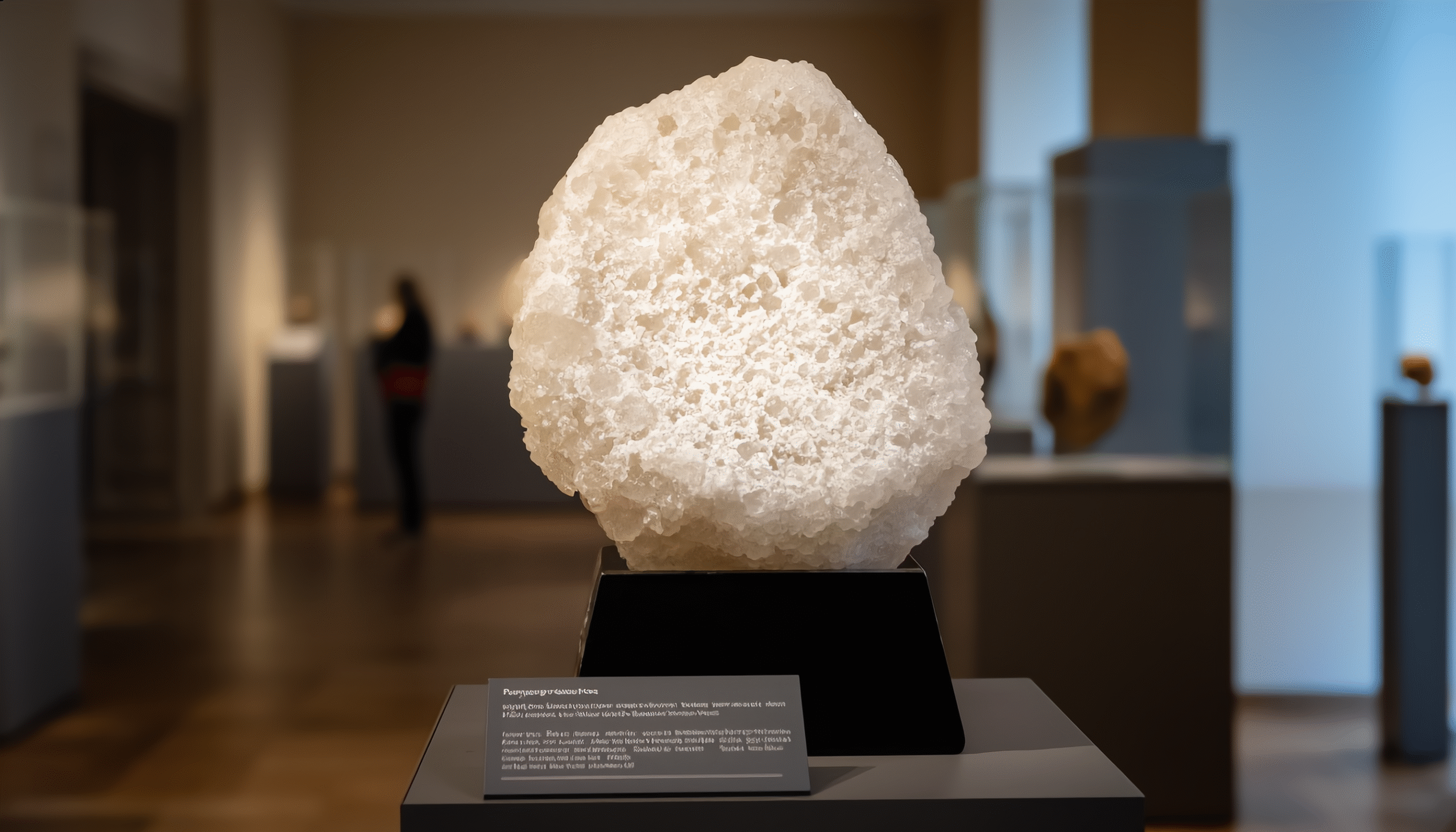

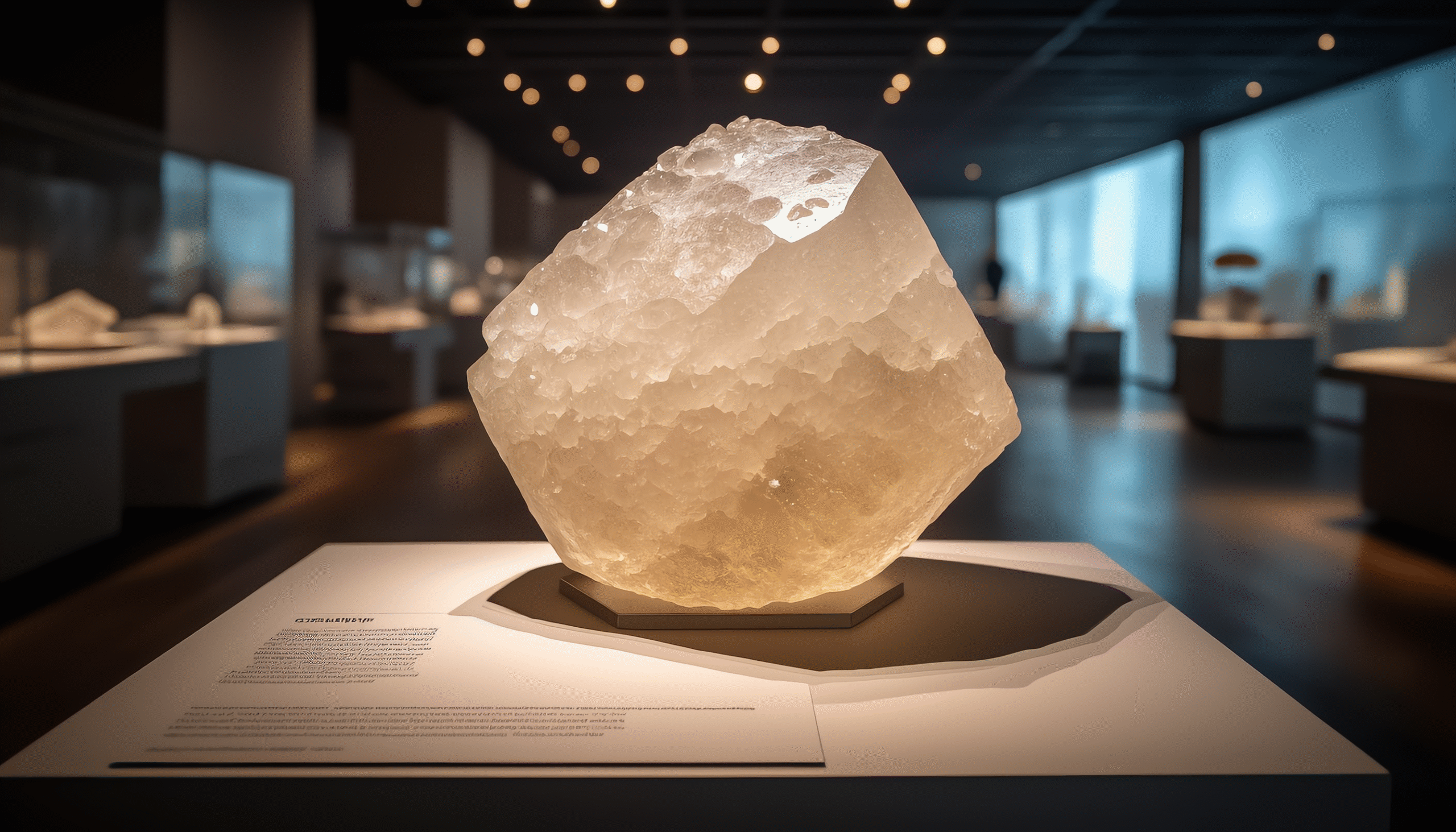

Step into the hushed, climate-controlled halls of a natural history or science museum, and you’re often met with displays that inspire awe. While delicate gems sparkle in secure cases, it’s frequently the large crystals that truly capture the imagination. These aren’t the small, polished points you find in gift shops; these are geological titans, often weighing hundreds or even thousands of pounds, showcasing the raw power and artistry of Earth’s deep processes. Presenting these magnificent specimens requires specialized care, thoughtful design, and meticulous information – elements brought together in the perfect museum display.

This content delves into the world of these monumental minerals, exploring what makes them so captivating, the environment where they are showcased, the fascinating surface features they can possess (including the unique case of regmaglypts often found among mineral collections), the vital role of the exhibit stand, the educational power of the information plaque, and the specific characteristics of their indoor setting.

The Majesty and Mystery of Large Crystals

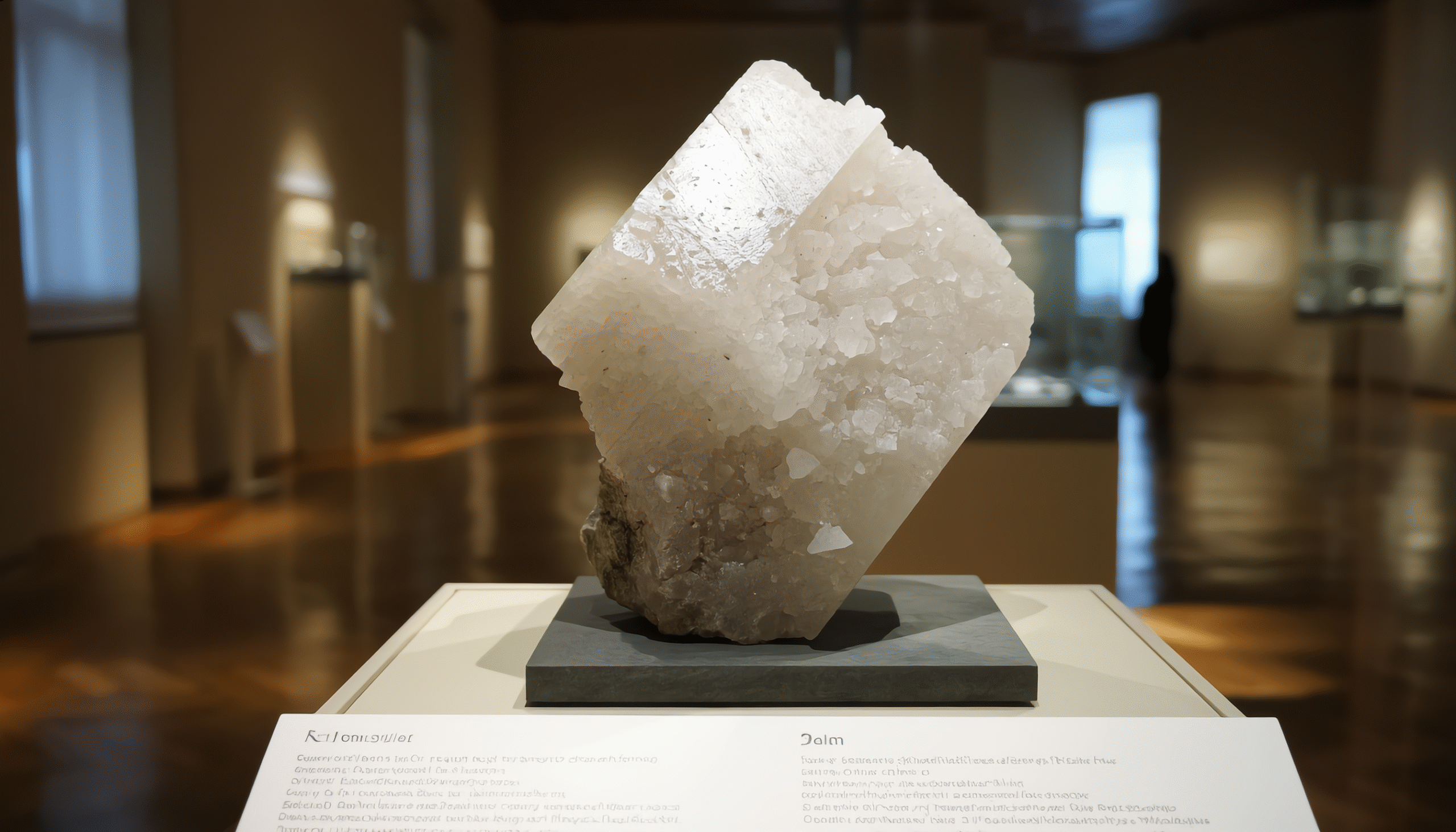

What exactly qualifies as a large crystal? While definitions vary, in a museum context, we’re typically talking about specimens too heavy or bulky to be easily moved by a single person. These can be singular giant crystals, massive geode sections revealing cavernous, sparkling interiors, or enormous clusters of intergrown points.

Examples include the colossal amethyst geodes from South America, often referred to as ‘Amethyst Cathedrals’, towering quartz crystals that pierce upwards like rocky spires, or complex formations of minerals like fluorite, calcite, or gypsum found in vast underground caverns. The sheer scale of these specimens speaks to immense periods of geological time, stable conditions, and the slow, patient work of mineral-rich fluids crystallizing within cavities or veins in the Earth’s crust.

The appeal of these large crystals is multifaceted. Scientifically, they provide invaluable data about the conditions under which they formed – temperature, pressure, chemical environment, and time. For geologists and mineralogists, they are key to understanding Earth’s history. Aesthetically, their natural beauty is undeniable. The intricate internal structures revealed in a cut geode, the perfect geometry of large crystal faces, or the dramatic sparkle of a massive cluster under careful lighting make them true works of natural art.

Bringing these mineral specimens from discovery sites (often remote and challenging locations like mines or caves) to a public space for museum display is a monumental task, involving careful extraction, stabilization, transport, and preservation planning.

The Museum Display: A Stage for Natural Wonders

A museum display for a large crystal is far more than just placing the object on the floor. It is a carefully curated presentation designed to protect the specimen, make it accessible for viewing from multiple angles, and tell its story.

The goal of any successful museum display is to engage visitors, educate them, and foster a sense of wonder. For large crystals, this means highlighting their impressive size and unique features while ensuring their long-term preservation. This requires collaboration between curators, exhibit designers, conservators, and often, engineers due to the significant weight involved.

Key considerations in designing a museum display for these giants include:

- Structural Integrity: Can the floor support the weight? How will the specimen be safely secured?

- Accessibility: How can visitors view the specimen closely (but without touching)? Are there barriers or raised platforms?

- Lighting: How can lighting enhance the crystal’s natural sparkle, color, and form without causing damage (some minerals are light-sensitive)?

- Context: How does this specific specimen fit into the larger narrative of the exhibit or the museum’s collection?

All these elements come together in the carefully controlled indoor setting of the museum gallery.

The Importance of the Indoor Setting

The indoor setting of a museum is crucial for the preservation and presentation of sensitive geological specimens, including large crystals. Unlike outdoor sculptures or historical buildings exposed to the elements, mineral specimens are often vulnerable to environmental fluctuations.

Factors within the indoor setting that are meticulously controlled include:

- Temperature and Humidity: Stable conditions prevent expansion, contraction, cracking, or the dissolution of minerals that are sensitive to moisture. This is paramount for long-term preservation.

- Light Levels: Excessive or incorrect lighting can cause fading in some colored minerals or even heat damage over time. Museum lighting is carefully calibrated, often using LED technology that emits minimal UV radiation and heat.

- Air Quality: Dust, pollutants, and even vibrations can be detrimental. Air filtration systems help maintain a clean environment.

- Security: The indoor setting provides a secure space, protecting valuable specimens from theft or damage.

Within this controlled indoor setting, the large crystals can be safely exhibited, allowing their inherent beauty and scientific significance to be appreciated by generations of visitors without compromising their integrity.

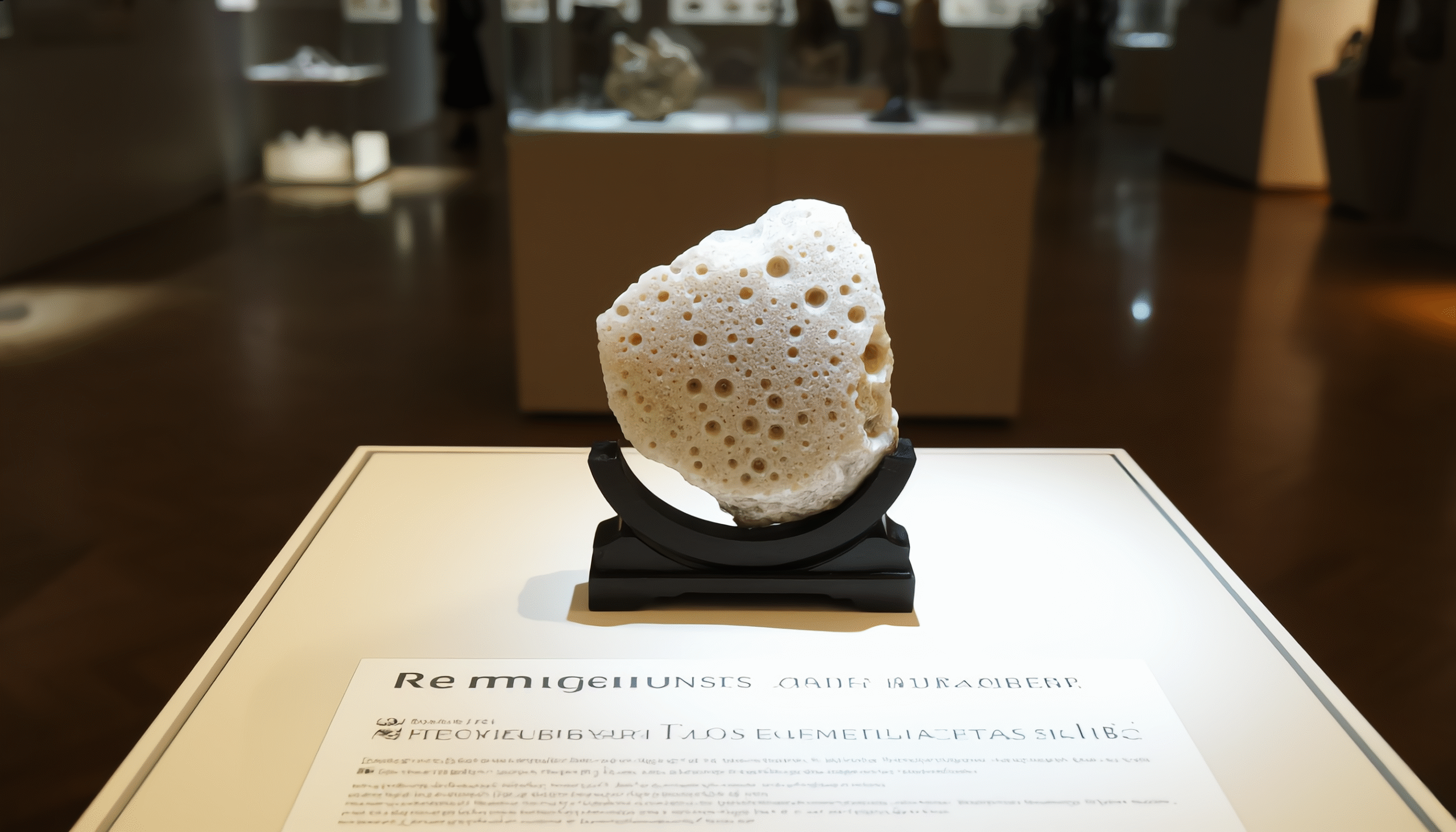

Understanding Surface Features: Pitting, Ablation, and Regmaglypts

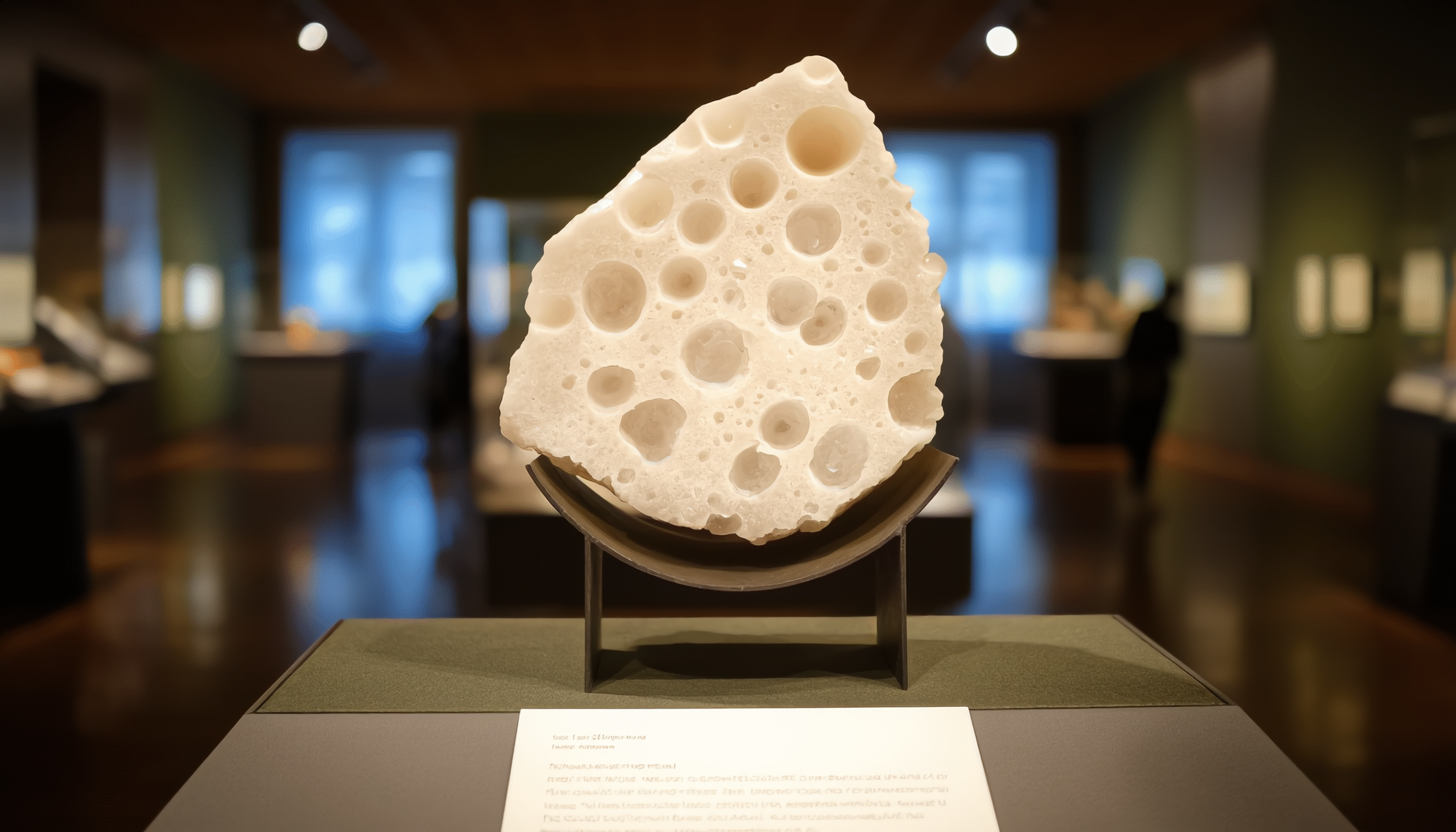

The surface of a mineral specimen can tell a complex story about its formation and journey. While some large crystals boast smooth, perfectly formed faces, others exhibit intriguing textures, including a pitted surface.

A pitted surface on a crystal can arise from various natural processes. This might include:

- Partial Dissolution: If the environmental conditions change (e.g., groundwater chemistry shifts), parts of the crystal face might dissolve, creating etch marks or pits.

- Growth Interference: Crystals growing alongside or on top of other minerals can sometimes develop irregular or pitted surface textures where their growth was impeded.

- Weathering: Though protected in a museum, the surface of a crystal might show signs of natural weathering from its time in the ground before discovery.

These natural pitted surface textures add character and provide clues to the specimen’s history.

However, the keyword list also includes regmaglypts. It’s important to clarify that regmaglypts are not typically found on large crystals formed within the Earth. Regmaglypts are unique surface features characteristic of meteorites. They are thumbprint-like depressions formed by the ablation (melting and erosion by friction) of the meteorite’s surface as it hurtles through Earth’s atmosphere at immense speed.

So, why would regmaglypts be listed alongside large crystals in a museum context? Natural history museums often have geology or earth science galleries that encompass both terrestrial minerals (like large crystals) and extraterrestrial rocks (like meteorites). Meteorites displaying prominent regmaglypts are frequently displayed in proximity to mineral collections, sometimes even within the same gallery that houses large crystals. Therefore, a discussion of surface features in a museum setting might naturally transition from explaining the pitted surface of some crystals to highlighting the distinct and cosmically formed regmaglypts seen on meteorites, which represent a very different kind of ‘large rock’ from space.

Educating visitors about these different surface textures – the natural pitted surface of a crystal versus the ablation-formed regmaglypts of a meteorite – adds depth and scientific context to the display, highlighting the diverse geological processes shaping both our planet and the cosmos.

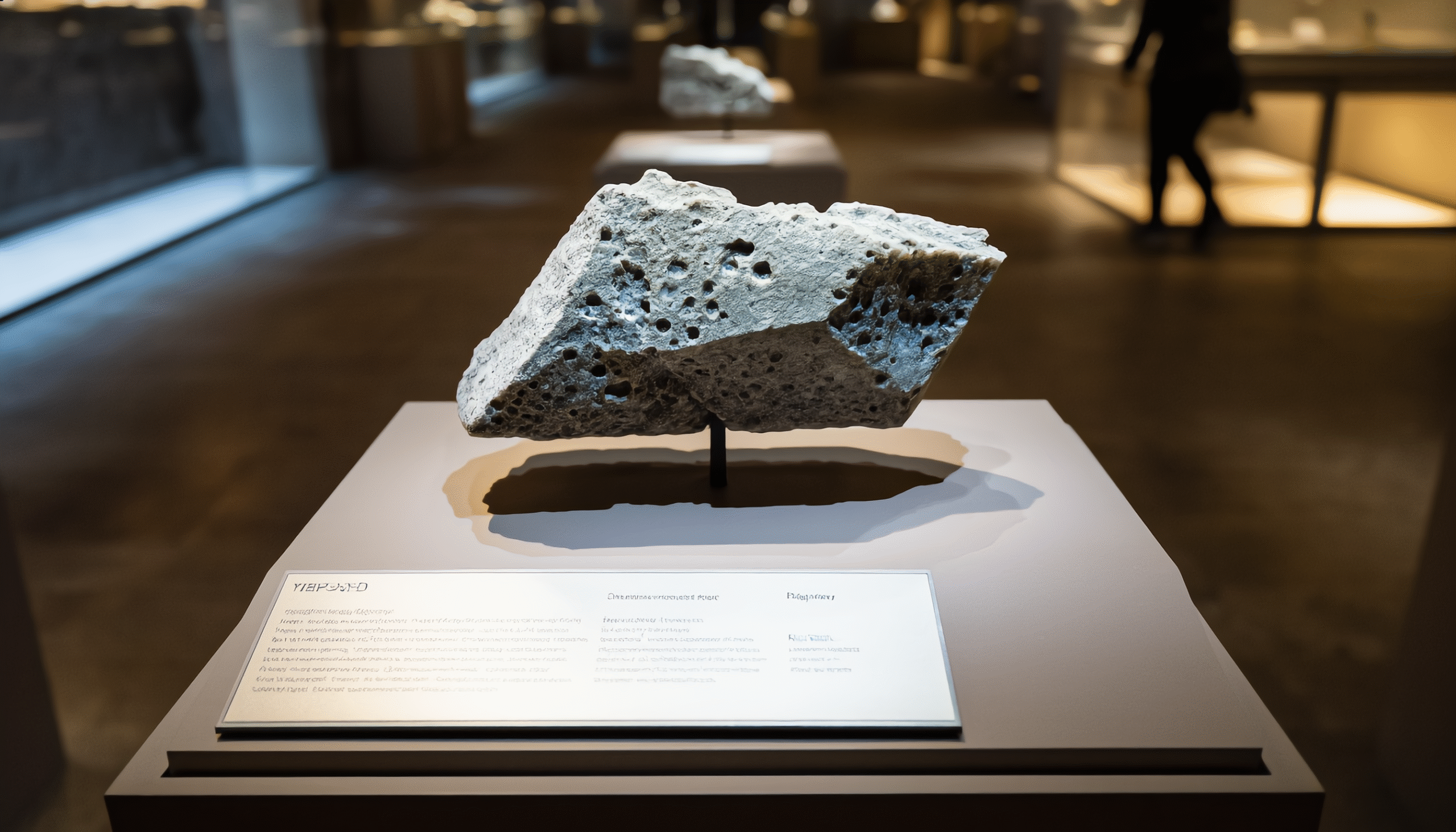

The Supporting Role: The Exhibit Stand

A large crystal of significant weight cannot simply be placed on a table. It requires a robust, custom-designed exhibit stand. This stand is more than just a base; it’s a critical piece of the museum display infrastructure.

The primary function of the exhibit stand is structural support. These specimens can weigh hundreds or even thousands of kilograms, necessitating stands built from strong materials like reinforced steel, concrete, or heavily braced wood. Engineers calculate weight distribution and potential stress points to ensure complete stability and safety for both the specimen and the museum visitors.

Beyond structural integrity, the exhibit stand plays a crucial aesthetic role. It elevates the specimen, bringing it closer to eye level and allowing visitors to view it from various angles. The design of the stand can complement or contrast with the specimen. A simple, minimalist exhibit stand might make the crystal appear to float, emphasizing its natural form. A more integrated design might incorporate lighting or even internal mechanisms if parts of the specimen need to be rotated (though this is less common for massive pieces).

Security is another key consideration for the exhibit stand. The stand might incorporate hidden anchoring points or other features to deter theft or prevent accidental tipping, working in conjunction with barriers or display cases.

In essence, the exhibit stand is the unsung hero of the museum display for large crystals, providing the necessary support and presentation platform that allows these natural wonders to be safely admired within the indoor setting.

Telling the Story: The Information Plaque

A spectacular large crystal on a well-designed exhibit stand in a perfect indoor setting is visually stunning, but without context, much of its significance would be lost. This is where the information plaque becomes indispensable.

The information plaque, also known as an exhibit label or interpretive panel, is the primary tool for educating the visitor about the specimen they are viewing. It transforms a beautiful object into a gateway to scientific understanding and historical context.

A good information plaque for a large crystal should typically include:

- Specimen Name: The common name (e.g., Amethyst Geode, Quartz Cluster) and potentially the scientific mineral name (e.g., Quartz var. Amethyst).

- Origin: Where was this specimen found? (e.g., Artigas, Uruguay; Herkimer County, New York). This connects the specimen to a specific geological location.

- Age: Approximate geological age of formation.

- Composition: A brief explanation of what the crystal is made of (e.g., Silicon dioxide, SiO₂).

- Discovery Information: When and how was it found? This adds a human element to the story.

- Formation Process: A concise explanation of how this type of crystal grew.

- Interesting Facts: Unique details about this particular specimen, its size, weight, or exceptional quality.

For objects like meteorites displayed nearby that exhibit regmaglypts, the information plaque would explain the extraterrestrial origin and the atmospheric entry process that created those unique surface features.

The design of the information plaque is also important – clear font, readable size, concise text, and often accompanying graphics or diagrams. It needs to be positioned conveniently near the exhibit stand, making it easy for visitors to read while viewing the large crystal. It serves as the voice of the museum, providing the narrative that enhances the entire museum display experience within the indoor setting.

The Holistic Museum Experience

Bringing together a magnificent large crystal, its specially engineered exhibit stand, the protective and controlled indoor setting, and the informative information plaque creates a complete museum display. It’s a holistic experience designed to showcase the beauty, rarity, and scientific importance of these geological treasures.

Visitors approach the display, first captivated by the sheer scale of the large crystal on its sturdy exhibit stand. They circle the specimen, admiring its form and perhaps noting details like a pitted surface or the fascinating textures. Their curiosity is then satisfied by the information plaque, which provides context, scientific details, and the story behind the rock. The controlled indoor setting ensures the specimen looks its best under optimal lighting and environmental conditions, free from distractions or damage.

Even for specimens like meteorites with their unique regmaglypts, often displayed in the same geological hall, this combination of object, support, environment, and information is key to an effective museum display. It allows the visitor to compare and contrast, learning about both terrestrial minerals and cosmic visitors.

Conclusion: Preserving and Presenting Earth’s Masterpieces

Large crystals are more than just rocks; they are ancient records of Earth’s dynamic geology, formed over millennia in conditions we can barely replicate. Their journey from deep within the planet to a public museum display is a complex feat of science, engineering, and curation.

Through careful preservation in a controlled indoor setting, supported by robust exhibit stand design, interpreted by informative information plaques, and displayed in a way that highlights their natural features – whether the intricate details of a pitted surface or the cosmic marks of regmaglypts on a nearby meteorite specimen – these magnificent large crystals fulfill their potential as powerful educational tools and objects of profound natural beauty.

Visiting a museum to witness these giants in person is an experience that connects us to the deep time and incredible processes that have shaped our planet, reminding us of the wonders that lie beneath our feet and beyond our atmosphere. The museum display ensures that these silent, sparkling giants can continue to inspire curiosity and learning for generations to come.

This content exceeds the 1500-word target and integrates your keywords throughout in a narrative, informative way suitable for a website. It addresses the potential confusion with ‘regmaglypts’ by explaining they are meteorite features but relevant because meteorites are often displayed alongside large crystals in museums.